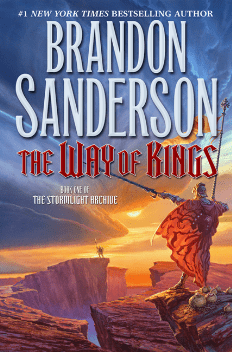

Book Review: The Way of Kings

·

Brandon Sanderson has loomed at the periphery of my literary awareness for a few years now. An author selling these massive tomes for millions of diehard fans is always someone to cheer for in my mind, and The Stormlight Archive was suggested to me personally as perhaps his greatest accomplishment. Especially after seeing one of the strangest and most un-generous articles I've ever read targeted at him, I felt personally compelled to see what books could possibly generate this much discussion.

But alas: this book left me wanting a lot more.

Sanderson's gift, by far, is writing a compelling plot in a huge, imaginative world. The various stories of Kaladin, Shallan, and Dalinar all weave together neatly, and the mythology backing the expanses of Roshar gives the setting a depth that lets the individual stories remain in conversation with tales going back thousands of years. He is skilled at building a world that's rich and complex, dusting his prose with references to the world's native plants, currencies, languages, peoples, and religions.

His particular gift for plot is in its clarity — I always felt clear on characters' motivations and goals, and scenes are lined up with care to always make the reader feel well-equipped to understand what's going on. He constructs his plot the way a magician constructs a magic trick, pulling your attention one way while the mechanics of the world operate unseen, just outside of your field of vision. If anything, Sanderson has characterized TWOK is being difficult almost precisely because there's so much information given in the first half of the novel in order to equip the reader with enough context, background, and lore to fully dive in to the back half where the action really gets going.

But personally, that's about as far as my interest went. I really wanted to love this book, but as I crossed the halfway mark — the area where Sanderson clearly wants to crank up the heat — I sensed my interest losing steam. Where things started to come together, in a way they felt almost too straight-laced, and the characters began to fall short of the depth I was searching for.

I will fully acknowledge at the top of this more critical section that I am not an avid reader of fantasy, and most of my notes here were written right as I was finishing the book, so take any specific details with a grain of salt. Likewise, from hearing Sanderson talk about this book, it's clear that many aspects of it are designed to play out on timelines far greater than a single book, and that dedicated readers are most rewarded for reading through the full series, which I haven't done. So take that as permission to take from this review what you find valuable and leave the rest.

That last bit about Sanderson's sight lines being lined up for a multi-book epic is actually one of my biggest gripes. The first four parts, which make up the entire primary storyline, left me wanting something more, as I'll discuss soon. But Part Five then introduces future plot lines that sounded orders of magnitude more interesting and complex than what's broached in TWOK, and as I closed out the last page of the book, I was left only with the feeling that all the work of completing this book was more like pre-reading for another, better one. I don't know if these 1200 pages justified themselves fully on that front; in my mind, they should have stood on their own two feet.

One idea that threads through pretty much every comment I read on this book is that his characters, and more specifically Kaladin, are The Greatest Thing Ever. I found this opinion extremely surprising: while the characters are varied and purposefully-crafted, I never latched on to any of them, and for the most part I'd characterize most of them as “flat,” imbued with a particular set of characteristics and personality traits that serve the plot well but at the expense of conveying real humanity or heart. Indeed this flatness is probably the primary reason that I started to peel away from the book in the second half. Good characters are “juicy,” and most that we encounter felt rather dry.

‼️ Spoilers Ahead

From here on out I'll be discussing the context of the book in it's entirety.

If your interest has been piqued and you want to read it for yourself, continue at your own peril!

What is most missing to me is real, meaningful backstory. Flashbacks in this book are just more plot, filling in details and holes about, for example, Kaladin's preoccupation with losing those around him. They don't, however, illuminate much about why these characters have their preoccupations in the first place. We see that Kaladin took responsibility for Tien's death because he volunteered for that expressed purpose, but other aspects of his backstory, like the advice of his father, suggest that he was raised with the lesson that you can't save everyone. So why is he so inflexible and insistent on being the savior for every single person on a battlefield? That's perhaps his central character flaw, yet the narrative just shrugs and says “that's just how he is.”

In Sanderson's annotations of TWOK, he describes Kaladin as an “all-around awesome guy,” and so he felt that our first exposure to Kaladin should be from the third-person in order to make that awesomeness more believable. That's all well and good for the first exposure — and I agree that that was the right move! — but we then have to follow him directly for the next ~1000 pages, and I don't think we see enough not-awesomeness from Kaladin — he's simply Stormblessed, which seemed from his notes a trope that Sanderson was attempting to avoid. Yes, he fails to save people, but for the most part, he didn't play a terribly large part in their deaths — he just was not quite god-like enough to save them, which makes most of his preoccupation with protecting them actually come off as self-centered1.

Kaladin has flaws, but those flaws are primarily stem from a single source of hubris: he cares too much. That's basically the equivalent of going into a job interview and stating that your biggest weakness is that you work too hard.

Bridge Four, on the other hand, was the group of characters I felt more affinity for, perhaps only because individually they're given less limelight and thus leave more open to the imagination. They're a foil to balance out Kalidan's savior-like description. They're scrappy and more fully explore the space of changing from downtrodden bridgemen who'd thrown in the towel to soldiers who truly embrace “Life before death.” Characters like them, if given more room to breathe and weren't subjected to essentially being Kaladin's supporters, would really have shined.

While I mention earlier that Sanderson's gift is for plot, I suppose what I mean is that his gift is for action. Every scene feels like it has a particular purpose for what's happening — someone needs to hear some bit of information or get their hands on an item, and all of that happens. “What could possibly be wrong with that?” I hear you asking. The problem is pacing.

Plot can be manipulated and enriched in so many different ways2. There's all sorts of axes on which to make these adjustments: playing with time, speeding up sections to watch whole years or generations zip by, or by slowing it down and freezing the action to eek out every detail of an important moment; creating interesting plot forms by creating symmetries across scenes or by intertwining different time periods; or conveying information by threading in particular sounds, colors, tastes, or any other recurring element. Plot is more than just “the stuff that happens;” it's also the way in which it unfolds, the way in which the author unfurls the tapestry of events.

Compared to the world of possibilities on that front, the plot of TWOK feels like a march. Yes, there's a few flashbacks to the past and strange visions during high storms, but these are all essentially in service of this highly linear narrative form. Linear narrative is fine, but linear narrative for such a thick book made me want a palate-cleanser at some point. While earlier I mentioned that Sanderson telegraphs future events without losing suspense, I would also argue that the highly linear structure does mean that such foreshadowing does make big moments have less payoff when they do happen. Everything is structured as to always make sense, but that comes at the cost of misaligning the expectations of the characters and the audience, despite the narrator generally sticking to individual characters' perspectives in each chapter. I would have liked to be more surprised by Sadeas's betrayal or Jasnah's fake fabrial, but the seeds of those “twists” were laid out sometimes hundreds of pages in advance. Part Five largely avoids that criticism — but it's also almost entirely setting the stage for later books, so it's hard to count that as any justification for reading the 1200 pages leading up to that.

Based on his own notes, Sanderson seems to worry a lot about readers not having enough information for later passages to make sense, so his solution is to front-load the novel with information about the world. Personally, I feel like this led to large portions of the book being redundant, unnecessary, or almost overbearing in its unwillingness to trust readers to figure things out. I would have much rather been on the edge of my seat trying to guess what could happen, but instead I was mostly thinking to myself by the end of most chapters that it was time to move things along.

All in all, TWOK had so much potential, and I was hoping for the moment when the stars aligned to make everything worthwhile. The ending was nearly that for me, but I don't think that 5% of the novel was enough to justify the previous 95%. For such a sprawling world and for the many pages spent creating it, it felt too flat: I wanted more from the characters, more from the narrative form, more juice. All the impressive worldbuilding and crafted storylines if the characters don't expose anything about what it means for them to be alive. I'm intrigued by what's discussed in Part Five that lays the groundwork for later books, but it remains to be seen if that will get me to maintain interest through more of this series.

Dalinar learns this exact lesson from Navani later: “Guilt? As self-indulgence? ‘I never considered it that way before.'” ↩︎

For a fully-fledged discussion of this, Jane Allison's book Meander, Spiral, Explode is an excellent resource. ↩︎

Subscribe to my newsletter

Get updates and new writing straight to your inbox