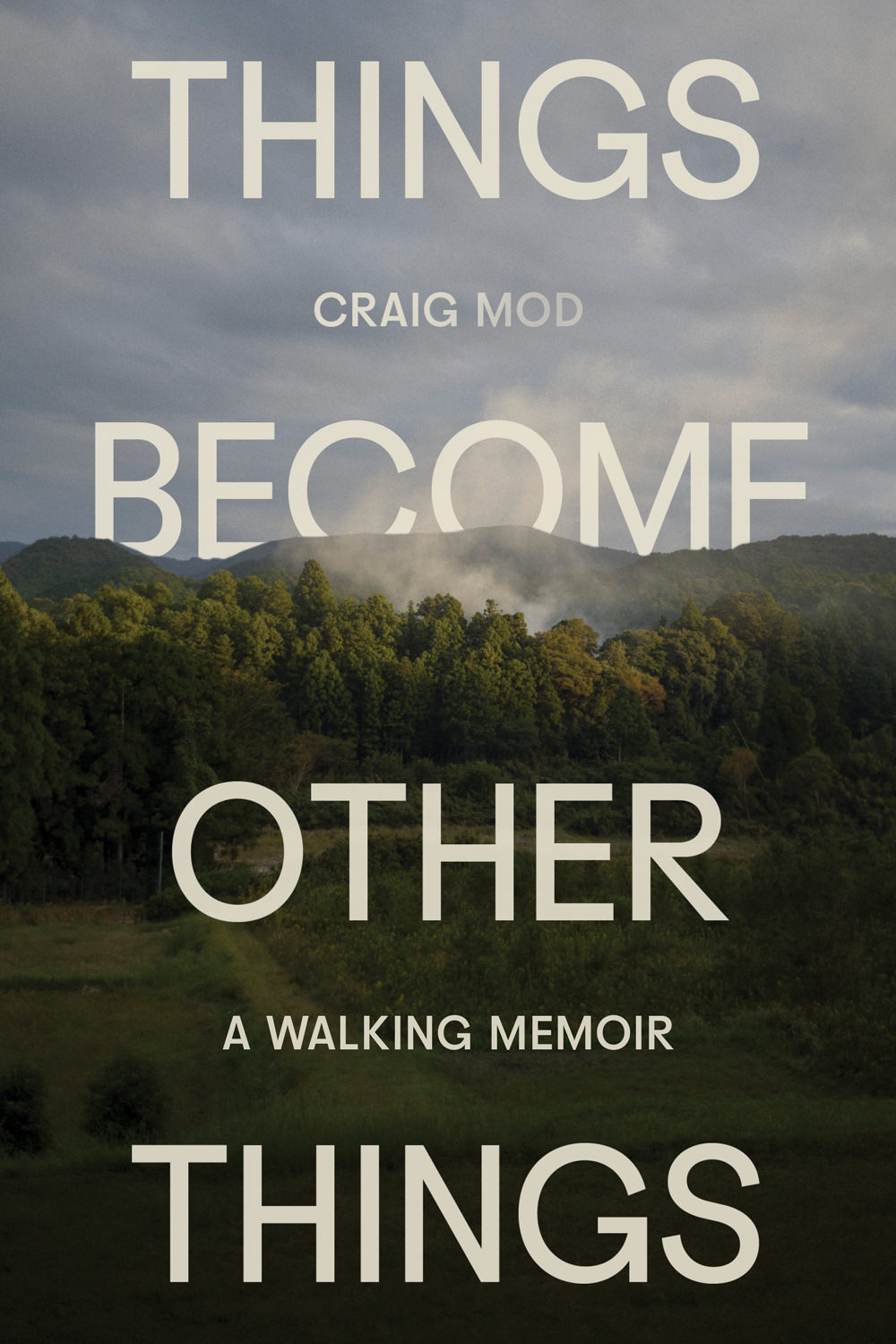

Book Review: Things Become Other Things

·

"I hold on to the hope that contrition is fixed within the steps of the very

walk itself. Each step, an apology. A million apologies. I want to kiss the

foreheads of everyone I see."

A quick story of my own before we get to the book:

I can barely feel my legs. The day started with a vertical march: five kilometers of hills. Hills so steep that even hundreds of years ago, when pilgrims far tougher than I walked these routes, they nicknamed it the "body-breaking slope."

At that point of exhaustion, with a heavy back and legs shot even before starting, my mind burns so hot with pain that it becomes empty. It almost inverts itself to the pain: the more miserable I am, the simpler the world becomes. The cool January air stings my lungs. Everything pares down to its plainest form: pressure, sensation, heat.

An hour later, a sign marks the top of the pass. I threw down my pack and leaned back against one the many cedar trees that populate the interior of the Kii peninsula. I put my hands on its trunk. Trees can grant you a little boost of energy, if you ask nicely.

Mom used to do that too, put her hands on tree trunks, giving them a hearty pat. She spoke to plants like friends, offering them help when they drooped or whispering sweet nothings when they bloomed. I started doing the same on these hikes. Every time I think of her.

There against the cedar tree, I see her walking in front of me, hear her whispering to the trees, her voice merging with the soft murmur of leaves. I remember her at every shrine. I place coins down in her memory, bowing slowly.

Up ahead, the path flattens out, taking me across the top of the ridge. A sign marks it as the abode of the dead. I heard that souls pass through here, that they come to Amida-ji a short ways away to ring the temple bell before moving on. I don't know how, but I see her there, passing over the ridge just beyond the collapsed teahouse. I know that much to be true.

I pick up my pack and continue on my way. A temple bell rings in the distance. And again. And again.

Sometimes, a book feels like it was written just for me. Not just for my particular interests, but for me right here and now, with whatever suffering and joy and heartache is there. A book just for me-right-now: Craig Mod's Things Become Other Things.

TBOT follows Mod as he embarks on a long journey across the Kii peninsula in Japan, walking ancient pilgrimage routes and meeting kissa owners, farmers, fishermen, and loud-mouthed children. Along the way, he experiences an area in decline, harkening back to his industrial hometown.

This book is really an extended letter to Bryan, Mod's childhood friend murdered decades before but whose memory, in the quiet persistence of many weeks of walking, rises up and imprints itself. The trail, the people, old memories all intertwine, flow into and out of each other, forming vignettes depicting how places adapt — or fail to adapt — to economic decline, natural disasters, and the ever-shifting sands of time.

I also hiked this area -- albeit just for a few days, a small piece of Mod's total journey -- in January of this year, so the experience was fresh on my mind as I flipped through. Like Bryan's memory, I kept remembering Mom on this walk. Reading this book is a wonder in its own right, but for me personally it felt serindipitous, a sort of recontextualization of my own walk, a way of returning clear-eyed to the grief and love that bubbled up on those same footpaths.

Throughout the book, we meet a wide cast of characters. Some we glimpse for just a moment: an inn owner remembering his late wife, weather-beaten farmers enjoying a bath, an okonomiyaki shop owner who welcomes death. Each and every one of their perspectives articulate the contours of a world constantly undergoing change. Mod handles all of them with care. On this front, it's especially refreshing that Mod describes their actions and translates their speech completely without pretense, without the awkward othering and mystique that's often used by Westerners to describe life in Japan. Every person we meet appears in full-color:

As the husband drives me down off the mountain, back to the Ise-ji path, he breaks our silence by saying, She ain't ... our daughter.

[...]

She just appeared seven years back. Wanderin' the country, needin' a job, somehow ... found us. Not a daughter, but like a daughter. Time passes, life moves, and that's what happens: Things become ... other things.

Brief conversations like this -- in the car, ordering food, walking past a rice field -- illuminate a group that, despite its decline, is supported and seen. Their lives can be hard, absolutely. Once-bustling kissas are now empty (save for Mod with a plate of pizza toast), fishermen's hauls get smaller every year. But there's never a sense of not-enough. The inn owners still feed Craig huge stacks of pancakes and send him off with five loaves of bread, small shops get picked up by the family's next generation. Things continue on, become other things.

If only Bryan could have seen all of this. Maybe, Mod writes, their lives would have been different. The sense of scarcity so absent from Craig's walk was by contrast a defining characteristic of his childhood. He recalls fights, drugs, the boys' desire to buy a gun. He recalls one of his classmates: "We knew a kid who got a plastic sandwich bag thick with hash for Christmas, carried and unveiled it proudly. I visited his house once. They owned no furniture."

"This world turns and turns and the more I move my feet the more I believe in

things we never understood. Life, irrepressible, it billows over the top of

the pot, man. Let me be your eyes as best I can. I'll bear witness to this

wonder you never got to see."

And so Mod balances these two worlds, the memories in his mind binding together with the roads under foot. He threads one word throughout these chapters: yoyū, "the excess provided when surrounded by a generous abundance." This heart-quality, this space is what facilitates healing. It's what allows communities to bend and not break. Something those two young boys never saw.

And it's through all of these lenses -- abundance, loss, decay, penance -- that Mod connects his past and present. The monotony of the walk, one foot in front of the other, gives rise to new worlds, to hope and joy and a deep, wide love. I went to an event for this book's release, and the final question of the night from the audience was "What's the secret to an interesting life?"

Craig smiled and leaned in. "Full days."

Subscribe to my newsletter

Get updates and new writing straight to your inbox